A White Man’s Empire: The United Stated Emigrant Escort Service and Settler Colonialism during the Civil War

It is hard to deny that immigration is one of the most contentious political issues of our time. In the years since the 2016 presidential election, the use of xenophobic and nationalist language to support restricting immigration has become increasingly common, even coming directly from the Oval Office. Critics have accused the current administration of racist immigration policies, ranging from the so-called “Muslim Ban” in 2017 to the continued incarceration of thousands of migrants along the U.S. border, the increasing restrictions on asylum status, and cuts to refugee resettlement quotas. Although the United States has not always been hostile towards immigration, its migration policies have long been xenophobic. Even the historical instances in which the U.S. government has encouraged immigration and migration reveal precedents to modern xenophobia and nationalism. While in 2020 nationalist rhetoric drives policies that limit immigration, Civil War era nationalism fueled support for migration to the American West and fulfilled a desire to ensure white settlement in areas under the control of American Indians.

During the Civil War, the United States actively encouraged the immigration and migration of white people as part of its empire-building mission in the American West. As Alison Clark Efford’s recent review essay on empire and immigration in the Journal of the Civil War Era demonstrates, historians are increasingly analyzing the Civil War era with an imperial framework.[1] This trend is reflected in recent posts on this blog contending that the Civil War was a war for settler colonialism, which “requires the removal of Indigenous people in order for settlers to permanently occupy the land.”[2] Migration policies were an important part of the settler colonial effort. The federal government’s concern about migration, even as the nation descended into civil war, is evident in the number of influential policies promoting westward migration established between 1861 and 1865. While the Homestead Act and the Pacific Railroads Act, both passed in 1862, are the most well-known examples of wartime legislation encouraging westward migration, another lesser known federal government initiative, the United States Emigrant Escort Service, played a valuable role in sustaining migration to the West as battles began to rage in the East.

An act of Congress in March 1861 established the United States Emigrant Escort Service “for the protection of emigrants on the overland routes between the Atlantic Slope and the California and Oregon and Washington frontier.”[3]Many congressmen supported the Emigrant Escort Service following the Utter-Van Ornum emigrant train massacre in September 1860, which left 29 of 44 emigrants murdered, and several captured by the American Indians who allegedly perpetrated the attack. The act afforded emigrants with a military escort providing “protection not only against hostile Indians, but against all dangers, including starvation, losses, accidents, and the like.”[4] It was passed the same day as numerous other bills designed to facilitate white settlement in the West, including bills to create the Territory of Dakota and survey its land, to organize the Territory of Nevada, and to complete geological surveys in Oregon and Washington Territory.

Medorem Crawford, an emigrant to Oregon in 1842, accepted an appointment as Captain of the Emigrant Escort Service in April of 1861. Since westward migration routes were so varied, Crawford and his soldiers would guide emigrants west from Omaha, where many believed the route became more dangerous. Crawford guided the emigrants along the California-Oregon Trail until the trails split, after which point numerous soldiers with the agency would guide smaller groups as they split up along the various trails to California, Washington, and Oregon. In 1862 Crawford reported that “no emigrants have at any time been troubled by Indians while in the vicinity of my company,” although he felt many likely would have run into trouble along the route “had it not been for the protection afforded them by the Government.”[5] The United States Emigrant Escort Service escorted over 10,000 white emigrants west in the fall of 1862 alone.[6]

As more and more emigrants traveled west under military escort, tensions with numerous Indigenous nations intensified, especially those with lands along emigrant routes. Tensions were especially high with the Northern Paiute, Bannock, and Western Shoshone bands, referred to by whites as “Snake Indians” after the Snake River that runs through their lands. White migrants repeatedly accused Snakes of perpetrating violence along emigrant roads, though numerous captains in the Emigrant Escort Service emphasized that only those who strayed too far from the main train escort met violence from Indigenous peoples or other white emigrants.

William Pickering, Governor of Washington Territory, demanded the punishment of American Indians accused of violent confrontations with white emigrants, lamenting the “terrible human butchery of our own white American population of men, women, and children” as they attempted to travel West.[7] Pickering believed crimes against white emigrants needed to be avenged, and urged the Army to conduct retaliatory expeditions against the Snakes in 1863, led by captains from the Emigrant Escort Service, Medorem Crawford and Reuben L. Maury. Pickering also encouraged increasing federal government protection of emigrant routes until it completely deterred “any black hearted redskin or whiteskin devils in human shape from injuring or jeopardizing either the life or limb or property of any one man, woman, or child who may desire to travel across any part of the soil of the United States between the Missouri and the Columbia Rivers.”[8] As Pickering’s nationalist vision indicates, he believed that white emigrants had the right to travel and settle where they pleased, without regard to or interference from the people on whose land they were settling. The Emigrant Escort Service played a key role in this vision by providing military protection to westward migrants, and although it diverted soldiers that could have been used to fight the Confederacy, the service was a fundamental component of nationalist migration policies that promoted permanent white settlement in the American West during the Civil War. The service led expeditions again in 1863 and 1864, demonstrating how these nationalist policies continued, even in spite of the Civil War, for the sake of settler colonialism.

The United States Emigrant Escort Service operated from 1861 to at least 1865. Major General Grenville M. Dodge reported that in the summer of 1865, in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, nearly 12,000 emigrants passed through Nebraska headed out West. Nonetheless, the end of hostilities in 1865 brought renewed focus on the settler colonial project in the West, and the necessity for a traveling escort system would soon be largely replaced by the scores of garrisons and forts built throughout the West. By the end of the decade, the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad made an escort detail nearly obsolete.

Although the United States Emigrant Escort Service was a short-lived initiative, it had lasting effects. In late 1865 General Dodge wrote that the protection of emigrant roads during the Civil War had produced an “immense yearly emigration which is forming a mighty empire now nearly in its infancy.”[9] The Emigrant Escort Service, especially alongside other initiatives like the Homestead Act, reflects the larger objectives of the war as a war for settler colonialism, and represents the implementation of migration policies designed to create an empire for the benefit of white emigrants. Like language surrounding efforts to encourage immigration and migration westward during the Civil War era, the increased restriction of immigration under the current administration is largely discussed in nationalist and xenophobic terms. Although different times and different circumstances may have prompted different measures, United States migration policies remain influenced by nationalist and xenophobic rhetoric, like that which led to the formation of the Emigrant Escort Service over 150 years ago

[1] Alison Clark Efford, “Civil War-Era Immigration and the Imperial United States,” The Journal of the Civil War Era 10, no. 2 (June 2020): 233-253.

[2]Michelle Cassidy, “The Contours of Settler Colonialism in Civil War Pension Files,” Muster: The Blog of The Journal of the Civil War Era, published June 28, 2019, accessed April 21, 2020, https://www.journalofthecivilwarera.org/2019/06/the-contours-of-settler-colonialism-in-civil-war-pension-files/. See also Paul Barba, “A War for Settler Colonialism,” Muster: The Blog of The Journal of the Civil War Era, published March 3, 2020, accessed April 21, 2020, https://www.journalofthecivilwarera.org/2020/03/a-war-for-settler-colonialism/. For more on settler colonialism see Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (December 2006): 387-93.

[3] The final Army Appropriations Bill for 1862 (H.R. No. 899) had an amendment attached which provided $50,000 for the United States Emigrant Escort Service. For the debate on the Emigrant Escort Service amendment see 36th Cong, 2nd session, Congressional Globe: Containing the Debates and Proceedings of the Second Session of the Thirty-Sixth Congress, Also, of the Special Session of the Senate (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Globe Printing Office, 1862), 1212-3, 1219, and 1249-51. See also Secretary of War Simon Cameron to Captain Henry E. Maynadier, April 4, 1861, in The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I, Volume 50, ed. United States War Department (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), 460 (henceforth OR series: volume).

[4] Secretary of War Simon Cameron to Captain Henry E. Maynadier, April 4, 1861, OR I:50, 460.

[5] Medorem Crawford, “Report on the Emigrant Road Expedition from Omaha, Nebr. Ter., to Portland, Oreg., June 16-October 30, 1862,” OR I:50, 155.

[6] Crawford, “Report on the Emigrant Road Expedition.”

[7] William Pickering to General George Wright, October 21, 1862, OR I:50, 189.

[8] William Pickering to General Benjamin Alvord, October 18, 1862, OR I:50, 182.

[9] Major General G. M. Dodge to Lieutenant Colonel Joseph McBell, November 1, 1865, OR I:48, 343.

Stefanie Greenhill

Stefanie Greenhill is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Kentucky. She is completing a dissertation on refugees who fled from the Confederacy under duress during the Civil War, entitled, “Escaped from Dixie:” Civil War Refugees and the Creation of a Confederate Diaspora.

Scott Hancock, Gettysburg College, connects his own BLM demonstrations and reactions by often armed militia at the Gettysburg National Military Park with the lyrics of the Public Enemy’s 1990 title track in a post entitled “

Scott Hancock, Gettysburg College, connects his own BLM demonstrations and reactions by often armed militia at the Gettysburg National Military Park with the lyrics of the Public Enemy’s 1990 title track in a post entitled “

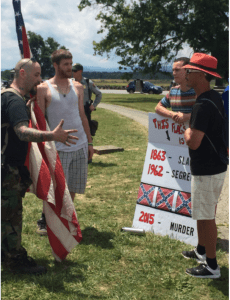

As the new century dawned, Klansmen continued to rally at Gettysburg. I spent nine summers working for the NPS as a seasonal interpretive ranger and remember walking by various KKK “1st Amendment” rallies. Klansmen planned a rally at Gettysburg in the fall of 2013, only to be canceled because of the government shut down. During the battle anniversary in 2017, a similar incident occurred when armed vigilantes and Klansmen descended upon the town reacting to another supposed Antifa threat. The event passed with relatively little notice, although a man from Shippensburg, Pennsylvania, one of the “militia men,” accidently shot himself in the leg.

As the new century dawned, Klansmen continued to rally at Gettysburg. I spent nine summers working for the NPS as a seasonal interpretive ranger and remember walking by various KKK “1st Amendment” rallies. Klansmen planned a rally at Gettysburg in the fall of 2013, only to be canceled because of the government shut down. During the battle anniversary in 2017, a similar incident occurred when armed vigilantes and Klansmen descended upon the town reacting to another supposed Antifa threat. The event passed with relatively little notice, although a man from Shippensburg, Pennsylvania, one of the “militia men,” accidently shot himself in the leg.