Fear of a Black Planet (Part I)

In 2013, the Confederacy returned to Gettysburg’s battlefield.

In 2015, the Confederacy took the town of Gettysburg.

In 2016, the Confederacy occupied the Peace Light Memorial on the battlefield.

In 2017, the Confederacy pledged allegiance to their flag on the Union side of the battlefield.

In 2019, like each November, the Confederacy marched through the streets of Gettysburg.

In 2020, the Confederacy won. Again.

In 2013, for the sesquicentennial, Gettysburg National Military Park invited visitors either to stand at the Union side of the battlefield’s Highwater Mark, or to gather on West Confederate Avenue, home of the Confederate state monuments, and walk the mile across the fields where Pickett gave the Confederacy’s last Gettysburg gasp (we thought) in that battle. As I recall, the numbers of participants far surpassed GNMP officials’ expectations. About three-quarters of visitors chose the Confederate side. And walked across the battlefield with many, many Confederate battle flags. Seeing images of that in USA Today and other national publications was when I wrote my first article about the Confederacy at Gettysburg and got the first threatening anonymous emails.

In 2015, returning from a trip two weeks after Rev. Clementa Pinckney, Tywanza Sanders, Cynthia Hurd, Rev. Sharonda Coleman-Singleton, Rev. Daniel Simmons, Rev. DePayne Middleton-Doctor, Susan Jackson, Ethel Lance, and Rev. Myra Thompson were assassinated at Emanuel AME church in Charleston, I drove through the Gettysburg town square on a rainy July Fourth. There were ten or so people, one who looked to be maybe 16 years old, in the middle of the square, several with Confederate flags reflecting on the wet pavement.

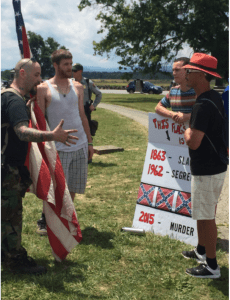

Three houses adjacent to our block put out new Confederate battle flags on their front porches. David Seitz, one of my neighbors and a communications professor at Penn State Mont Alto, mentioned to me that Confederate flags and monuments are a form of discourse, and it was all one-way in Gettysburg because nobody was speaking back. So for the next week, Bike Week, anticipating that there would be another display for the Confederacy, I asked my wife and daughter-in-law to employ their creative genius (because I have very little) to make a sign that speaks back. With a nauseous, clenching stomach, I biked up to the square from my house. Sure enough, several people, decked out in period gear, were waving large Confederate flags. I took my sign and occupied one small corner of the square, accompanied at various points by my son, my daughter and her husband, and my wife.

During the biker parade, I’d say the majority expressed support for the Confederate flags. A significant minority did likewise for us—the most memorable being the group of all-black bikers who cursed out the Confederate flaggers and gave us thumbs up as they roared by. Several people talked with us; most of them disagreed, but with civility.

In 2016, when the Sons of Confederate Veterans reinvigorated March’s CSA Flag day at the Peace Light, I applied for a permit to stand there with my family and my sign. Other folks, most of whom live in Gettysburg and a few from nearby areas, heard about it. About 80 of us turned out to speak back to the almost 200 SCV supporters.

In 2017, in response to a nonsensical rumor that Antifa was coming to desecrate non-existent Confederate gravestones at Gettysburg and burn flags, armed militia and their armed sympathizers took over the battlefield. I applied for a permit, set up a chair, water and my sign, and heard the gunshot later in the afternoon when one man accidently shot himself in the leg about a hundred yards away. People were often dismissive, but not threatening. Some even debated at length; for a few months afterward, I exchanged emails with one debater.

In 2019, David Seitz and I, he with his homemade sign and me with mine, marched alongside the Confederate reenactors and their flags during the Remembrance Day parade in November. We wanted people to remember what this cruel war was all about. We got separated at some point. Some people quietly expressed agreement with me. More people cursed, told me to read a book; one shop owner stormed out of his store and yelled that I was wrong and did not know history; another organizer of the parade screamed at me from across the street to “take that sign down!” He and I, and several others, ended up having a long, polite conversation, and found a few points of agreement among many more points of disagreement.

In 2020 an armed woman said she would kill anyone she saw burning a flag. People with what appeared to be AR-15s spread out around us in flanking maneuvers. At the Virginia monument, people yelled at me and my friend Clotaire Celius, who is clearly much darker-skinned than me and my, as Caroline Randall Williams might call it, rape-colored skin, to go back to Africa, and to go get our welfare checks, and of course they employed the N-word. People told Jimmy Schambach and his father Jim, and Gavin Foster, my three white friends who came out to help, that white people like them made them sick. My friend Shawn Palmer, a black retired state trooper and more accustomed to always scanning his surroundings, observed one man at the Mississippi monument as he slowly walked up behind me and put his hand on the gun in his belt. People took pictures of our license plates. The bikers refused to drive by us, waiting until we finally pulled out, and then followed us for two and a half miles, riding nearly right onto Shawn’s bumper. A few hours later, one of them followed Shawn again. Soon after that, in the National Cemetery, about a half hour after armed men and their sympathizers forced out a white local pastor wearing a BLM shirt, Clotaire and I walked in. We were unaware of the pastor’s experience. An older white man holding an American flag lectured us about how we black people had a lot of problems and needed to fix ourselves. When I asked him if white Americans should do likewise among themselves, he—no doubt emboldened by the one hundred or so white people around the only two black men in the cemetery—said no. We walked off mid-lecture. As Clotaire then astutely observed, “Why are they so afraid of two black men? They have guns. We have phones.”

Public Enemy is still right. “All I got is genes and chromosomes” along with five friends outfitted in shorts, flip flops, water bottles, cell phones, a few 4” paper BLM flags from my ancient printer at home taped to 1/8” dowel rods, and two 28” x 22” signs in front of a forty-one foot concrete and bronze monument. With their AR-15s and assorted other guns, a few dozen people, “living in fear of my shade” plus truth and history, met us with anger and threats, unlike any other year the Confederacy has come back to Gettysburg. Fellow historians of every shade, we must respond.

Scott Hancock

Scott Hancock, associate professor of History and Africana Studies, came to Gettysburg College in 2001. He received his B.A. from Bryan College in 1984, spent fourteen years working in group homes with teenagers at risk, and received his history PhD from the University of New Hampshire in 1999. His scholarly interests have focused on Black northerners’ engagement with the law, from small disputes to escaping via the Underground Railroad, during the Early Republic and Civil War eras. He has more recently begun exploring how whiteness has been manifested on post-Civil War memorializations of battlefields. His work has appeared in anthologies and Civil War History, and he has published essays on CityLab, Medium, and The Huffington Post. He can be contacted at shancock@gettysburg.edu or on Twitter @scotthancockOT.

13 Replies to “Fear of a Black Planet (Part I)”

When you finally realize slavery in the Confederacy was a labor relation, not a race relation, your “fellow historians” might begin to be capable of responding. Until then, the America your “fellow historians” have left behind that has no clue about the right and wrong of the Civil War will haunt you as it does in your litany of cluelessness here.

There is certainly a naivete on the part of anyone who would dare write that slavery in the Confederacy was about labor relations. American slavery was always about a perceived superior race dominating a perceived inferior race. That is why they were chosen to be slaves. The color of their skin is exactly what made them inferior in the eyes of white people. There is no justifying enslaving anyone in a county that declared (and still declares) that “all men are created equal,” “that they are endowed by their creator,” and “liberty and justice for all.” (“The slaves were black, and racial inferiority was the dominant justification of white America’s system of chattel slavery.” From: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1066&context=etd.)

Wrong.

This is not a helpful comment. Maybe to you only. Derision only divides, but perhaps you are trying to do that. What litany of cluelessness [sic]? Are you actually coming down on the side of white privilege and white supremacy? Now THAT would be cluelessness [sic].

It is breathlessly clueless to look at this author’s list of events (all in the last decade) which regard Gettysburg as a holy (and rather comfortable) place for neo-Confederates, then wonder why. Especially from a “historian” who helped create such a welcoming environment at Gettysburg for neo-Confederates. There’s a reason these people like it there, and think it is their duty to “protect it”, a reason the author is indeed clueless about.

Fred, thank you for speaking up. It’s interesting that the author, who is obviously African American, was told he was clueless. His accomplishments say otherwise for sure.

Which author is “obviously African American”?

Thanks for your chronology of these events Scott and for trying to provide perspective to those who showed up at Gettysburg NMP and the Soldiers’ National Cemetery armed and spoiling for a fight. I am amazed at your calm and clear thinking in the midst of such open hatred. It was the saddest day in the history of both since the battle and the dedication of the cemetery. For those who do not understand the sign Scott holds I offer the following book related to the sad events of 2015 in Charleston, SC. Check out “Grace Will Lead Us Home:…” by Jennifer Berry Hawes. As I read this book I was sickened to realize that instead of our country being drawn together by this senseless act of hatred we are so much further apart 5 years later.

When I joined Scott at the 2019 Remembrance Day parade, I walked around with a sign that simply said, “‘States’ Rights’ = Slavery”. Here is a sample of the reactions I received from fellow Americans:

-Several people said to me: “Well, at least it kept black unemployment down!”

-A woman from New Jersey told me to “Go home!” (I live in Gettysburg.)

-“Jackass,” “A**hole,” “Libtard”… Etc.

-“Read a book!” (I asked which one, but got no replies.)

-“How much is George Soros paying you?”

-Families (including young children) staying at the 1863 Inn of Gettysburg yelled and booed at me from their hotel room balconies.

And so on…

Scott and I got separated and at one point I found myself surrounded by a small angry mob. I was very glad the police were within shouting distance. But I wasn’t afraid of these people, who were clearly small (figuratively speaking). Still, I was glad when Scott and I reconnected at my house and made sure we were both okay.

At the July 4, 2020 “false flag-hate rally” (as I call it), hundreds of Trump supporters and white supremacists openly carried AR-15s, handguns, and knives and patrolled the battlefield looking for “boogiemen”–the implication being that they would be willing to murder anyone who tried to harm a Confederate monument. In other words, they would kill other human beings in defense of stone and iron objects. The atmosphere was probably equivalent to that of the moments before a pogrom or lynching. I say that with all sincerity.

Why did my sign make people so angry? Why are there people ready to kill over monuments? These are questions I have been thinking about…

Ultimately, racism is at the heart of it all. Sometimes the racism is overt, sometimes it is subtler (as seen in some of the comments above). But all of this boils down to racism and white supremacy.

Thanks to you both for your actions. Your response itself, Mr. Seitz, would be a fine fifth blog post.

Thank you Mr. Noe. I appreciate the kind words and encouragement, especially from an expert in the field. Perhaps you, Scott, Peter, and I (and others) could connect somehow to discuss all of this further? Just a thought… Thanks again. Best, David