We’ve Always Been Here: Rediscovering African American Families in the U.S. Census

When I initially began examining United States Colored Troops (USCT) soldiers, I primarily focused on Civil War pension records. As previously noted, these rich primary sources can illuminate the forgotten lives of African Americans in many ways but do not (nor does any single historical record) tell the whole story of the lives of USCT soldiers and their kin. Since hundreds of thousands of people (for various reasons) never applied for a pension, other records fill in the archival silences. As a result, I turned to the U.S. Census to explore the complex living situations of USCT soldiers.

The U.S. Census is an excellent primary source that one can use to investigate the families of USCT soldiers before and long after their military service ended. Since many African Americans did not apply for pensions, the U.S. allows one to examine many people, regardless of their pensioner status. Another benefit to the source is that, due to the quantitative data collection of domiciles, it is possible to uncover a more nuanced understanding of household dynamics for people every decade. Thus, it becomes possible to locate numerous people, even across multiple generations, that do not always make appearances in other historical records. For instance, using the U.S. is plausible to trace fluid familial construction for William Butler (a Philadelphian-born Sixth the United States Colored Infantry soldier) before and decades after the Civil War. Thus, studying African American families has always been an available and accessible primary source.

Throughout the mid-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century, each iteration of the U.S. census asked for specific data on the nation’s inhabitants. Census enumerators asked for a multitude of information on each occupant that included (but was not limited to) an individual’s age, race, birthplace, marital status, full-time wage-earning occupational status, ownership of real or personal estate, literacy, the birthplace, and names of the individual’s parents, and some issues of mental illness. This quantitative information is exceedingly valuable in denoting how African American families fought against and continually adapted their living situations to protect and empower each other in their lifelong battle against racial discrimination.

Even with all the valuable data that the U.S. Census yields, it is important to recognize that there are significant issues in the historical record when attempting to study the families of USCT soldiers.[1] One of the most glaring problems with the source is how historically devalued the unpaid of women, regardless of their race. In many cases, census enumerators (sometimes conducting quick surveys) categorized women as either “keeping house” or holding no occupation at all. Such assessments ignored the important contributions that women made to their families, including but not limited to cooking, cleaning, gathering raw materials to create and sell goods in local markets, washing clothes, watching other people’s children, and bearing and raising their children. Additionally, some women successfully found seasonal and temporary wage-earning employment critical in keeping their families economically stable.[2] It is important to use critical analysis respectfully and accurately acknowledge how women contributed to their household in differing ways. Thus, a blank space in the U.S. Census often does not reflect how their families valued women. It is also critical to recognize that households sometimes included fictive kin—individuals that families treated as “kin” even if there were no adoptive, biological, or marital ties—for their household’s survival.[3] Even if the historical record or families explicitly state it, the continual opening of residences to non-blood-relative individuals says otherwise. Collectively, these examples highlight that using the U.S. Census requires a careful eye to acknowledge the complexity of African American households beyond the limited interpretation of a federal government record.

A brief examination of William Butler reveals how invaluable the U.S. Census to studying USCT veterans and their families. As his pension records denote, Butler enlisted in the Sixth United States Colored Infantry on August 8, 1863.[4] Unfortunately, on September 29, 1864, he was severely injured in the right thigh during the Battle at Chapin’s Farm in Virginia. After the conflict, a surgeon decided to amputate Butler’s right thigh. After receiving a medical discharge on May 29, 1865, Butler applied for and received an invalid pension of eight dollars per month. By 1866, Butler’s monthly pension payout increased to fifteen dollars after the pension agent categorized Butler as “totally disable,” implying that he would be unable to resume physically demanding, wage-earning work as a civilian. The Bureau of Pensions’ higher pension grading, at least, in this case, highlights that it realized that visible wartime wounds could hinder, if not eradicate, a veteran’s postwar employability.[5]

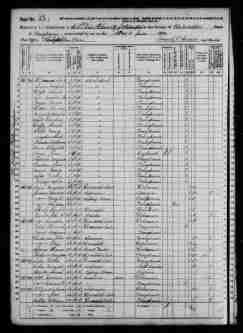

The U.S. Census thankfully fills in some gaps in his life. In 1850, Butler (along with Henry Anderson and Henry Johnson) lived as fictive kin in the Gilbert household. Robert and Gracy Gilbert undoubtedly appreciated the three men’s additional wages (working as a laborer, porter, and farm laborer, respectively) since the couple had two adolescent children. Gracy’s unpaid work and Richard’s wage-earning employment as a laborer made their financial stability difficult for the young family.[6] The bonds that these seven African Americans created reveal that familial definitions transcended blood and marriage. All three fictive were critical to keeping their household together, for themselves and each other.

Twenty years later, Butler was fictive kin in an interracial household with Alexander and Jane Elligood and Maggie Reagan. Alexander worked as a laborer. Both James and William were domestic servants, while Maggie (categorized as “unemployed”) found various ways to contribute to their residence. William’s occupation provides a unique avenue to examine gender since he performed a job that some people considered “women’s work.” Maybe he cared more about earning a wage than the gendered perception that some people may have had about working as a domestic servant.[7] At the same time, his employment reveals that even though a pension agent labeled Butler “totally disabled,” he performed physically demanding work, which brought him two forms of income when many African Americans struggled to establish one. Finally, this household was unique as Maggie, a white woman, cohabitated with African Americans when Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, had a well-established record of large and small-scale racial violence.[8]This household was aware, at some level, of the longstanding local racial tensions. Nevertheless, they instead focused on surviving and supporting each other.

While William Butler is not a representative case, but more an example of how to examine one’s life across multiple sources to uncover the pre-service and postwar life of a USCT soldier. The accessibility of the U.S. Census and the fact that many veterans and kin did not apply for a pension make it a valuable resource. Furthermore, in instances where there are pensions, it would behoove one to cross-reference with the U.S. Census to find more information about how African Americans constructed their lives in their unending battle against racial discrimination. In short, this federal government record offers another opportunity to understand and discuss who USCT soldiers were far beyond their time in the U.S. Army.

[1] Judith Giesberg, “ ‘A Muster-Roll of the American People”: The 1870 Census, Voting Rights, and the Postwar South,” Journal of Southern History 87, No. 1 (February, 2021), 38-41, 50-51; Margo Anderson, “The Missouri Debates, Slavery, and Statistics of Race: Demography in Service of Politics,” Annales de démographie historique, No. 1 (2003), 29-34.

[2] Nancy Folbre and Marjorie Abel, “Women’s Work and Women’s Households: Gender Bias in the U.S. Census,” Social Research 56 No. 3 (Autumn, 1989), 547-549.

[3] Edward Norbeck and Harumi Befu, “Informal Fictive Kinship in Japan,” American Anthropologist, Vol. 60, No. 1 (February, 1958), 102-117; Linda M. Chatters, Robert Joseph Taylor, and Rukmalie Jayakody, “Fictive Kinship Relations in black extended families,” Journal of Comparative Family Studies 25, No. 3 (Autumn, 1994), 297-312.

[4] Undated Pension Slip, in William Butler, Sixth USCI, pension file. National Archives Records and Administration, Washington, D.C.

[5] Kelly D. Mezurek, For Their Own Cause: The 27th United States Colored Troops (Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2016), 226; James Marten, Sing Not War: The Lives of Union & Confederate Veterans in Gilded Age America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 49.

[6] Seventh Census of the United States, 1850;(National Archives Microfilm Publication M432, 1009 rolls); Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[7] U.S Census Bureau, Ninth Census of the United States, 1870, M593 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1870).

[8] Please refer to the following studies on nineteenth-century racial discrimination (including violence) against African Americans in Philadelphia, Kali N. Gross, Colored Amazons: Crime, Violence, and Black Women in the City of Brotherly Love, 1880—1910 (Durham: Duke University, 2006); Leonard L. Richards, “Gentlemen of Property and Standing”: Anti-Abolition Mobs in Jacksonian America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1970); Daniel R. Biddle and Murray Dubin, Tasting Freedom: Octavius Catto and the Battle for Equality in Civil War America (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2010).

Holly A. Pinheiro, Jr.

Holly A. Pinheiro, Jr. is an Assistant Professor of History at Furman University. He received his bachelor’s degree (2008) from the University of Central Florida. Later, he earned his master’s degree (2010) and doctoral degree (2017) from the University of Iowa. His research focuses on the intersectionality of race, gender, and class in the military from 1850 through the 1930s. His monograph, The Families’ Civil War, is forthcoming June 2022 with the University of Georgia Press in the UnCivil Wars Series. You can find him on Twitter at @PHUsct.

One Reply to “We’ve Always Been Here: Rediscovering African American Families in the U.S. Census”